Tremendous homeland: Napoleon Bonaparte in our history

The author is a lawyer and university professor. Resides in Santo Domingo

- By LUIS R. DECAMPS

- Date: 04/20/2021

- Share:

Although between the island of Santo Domingo and France there is a distance of approximately 7 thousand two hundred kilometers and Napoleon Bonaparte always had Europe as a fundamental interest in his conquests, there was a brief period of time, at the dawn of the 19th century, in which he, angered by the course of events in the Saint Domingue colony, was compelled to turn his attention to this insular territory and, with the measures that he established, would significantly and drastically influence the course of its history.

Indeed, the implementation of the Haitian Constitution of 1801, among other reasons, definitively placed the governor "for life" Toussaint Louverture in a position of rebellion against France, and the response of Bonaparte, owner of power in the latter after the coup of State of Brumaire 18 of the year VII (November 9, 1799), was the dispatch of "the most formidable expedition that had ever crossed the Atlantic" (1), under the command of his brother-in-law, General Carlos Víctor Manuel Leclerc, to put down the rebellion of the “bandits” (2) in their colony on the island of Santo Domingo.

The expedition left Brest on December 14, 1801 and reached the island of Santo Domingo on February 2, 1802. It consisted of 50 ships with 21,000 sailors and 21,900 soldiers, later reinforced with an additional 15,645. for a total of 58 thousand 545 troops (3). As of that last month, a singular war would begin between the French and the former slaves of the western part of the island, since their tactic consisted of “avoiding any pitched battle… burning the ground under the enemy's own plants. and… attract it to places where the topographic disposition of the terrain meant some advantage for the defense ”(4).

Leclerc arrived on the island with precise instructions from Napoleon in matters of politics and military and administrative affairs. In this respect, the "first consul" of France had arranged that the general-in-chief of the expedition would be the captain general of the two colonies, and that in the eastern part a general commissioner and a commissioner of justice would be appointed, a general disarmament, there would be a division into dioceses and jurisdictions, and the management of commerce and justice would be different from that of the western part, which seemed to indicate that the Gallic ruler was not indifferent to the cultural and customary discrepancies that existed between the two peoples that inhabited the island.

Some of the main ideas of the reconquest expedition were exposed by Leclerc in three proclamations: in the first, of February 2, 1802, addressed to the inhabitants of the eastern part, he said that the best institutions are those that "are adjusted to the religion, customs, customs and language of the people for which they are made ", and promised" splendor, prosperity and tranquility "; in the second, of February 8 of the same year, addressed to the inhabitants of the western part, it stated that “by the French Constitution, Santo Domingo was part of the Republic, and that consequently this colony should not continue to be deprived of the advantages of belonging to a powerful nation like France ”; and in the third, on April 25, “he announced the granting of a provisional Constitution,

The war lasted more than three months (in which the many French were affected by tropical diseases, especially yellow fever) until the surrender of Toussaint, on May 6, 1802, "in conditions honorable for both parties", which, however, did not mean that there were no groups and insurgent leaders in various parts of the island (6). In particular, the promise of a provisional Constitution was not fulfilled, as spirits were raised when the law of May 20, 1802 was issued that reestablished slavery in the French colonies, which led to a revival of the struggle of the former slaves against the occupation troops (7).

Toussaint, whose surrender implied his retirement as a military leader while remaining free, was arrested in June of that same year during a luncheon which he was deceived (8) because the French authorities believed that he was the veiled leader of the insurgent rebels, and he would be sent to France as a prisoner, where he would die on April 7, 1803. However, the revolt would continue, now with the black troops under the direction of other leaders, among them his lieutenant Jean Jacques Dessalines. The new insurrectionary wave in the western part was a "war to the death." Increasingly weakened by disease and the ferocity of attacks by former slaves, the French (after almost 18 months of fighting) finally capitulated on November 18, 1803, abandoning the city of Cape Francés, last bastion of its already diminished dominion on the part of the West. The conflagration, according to eyewitness calculations, had cost France around 60,000 lives, and Saint Domingue 62,481 (9).

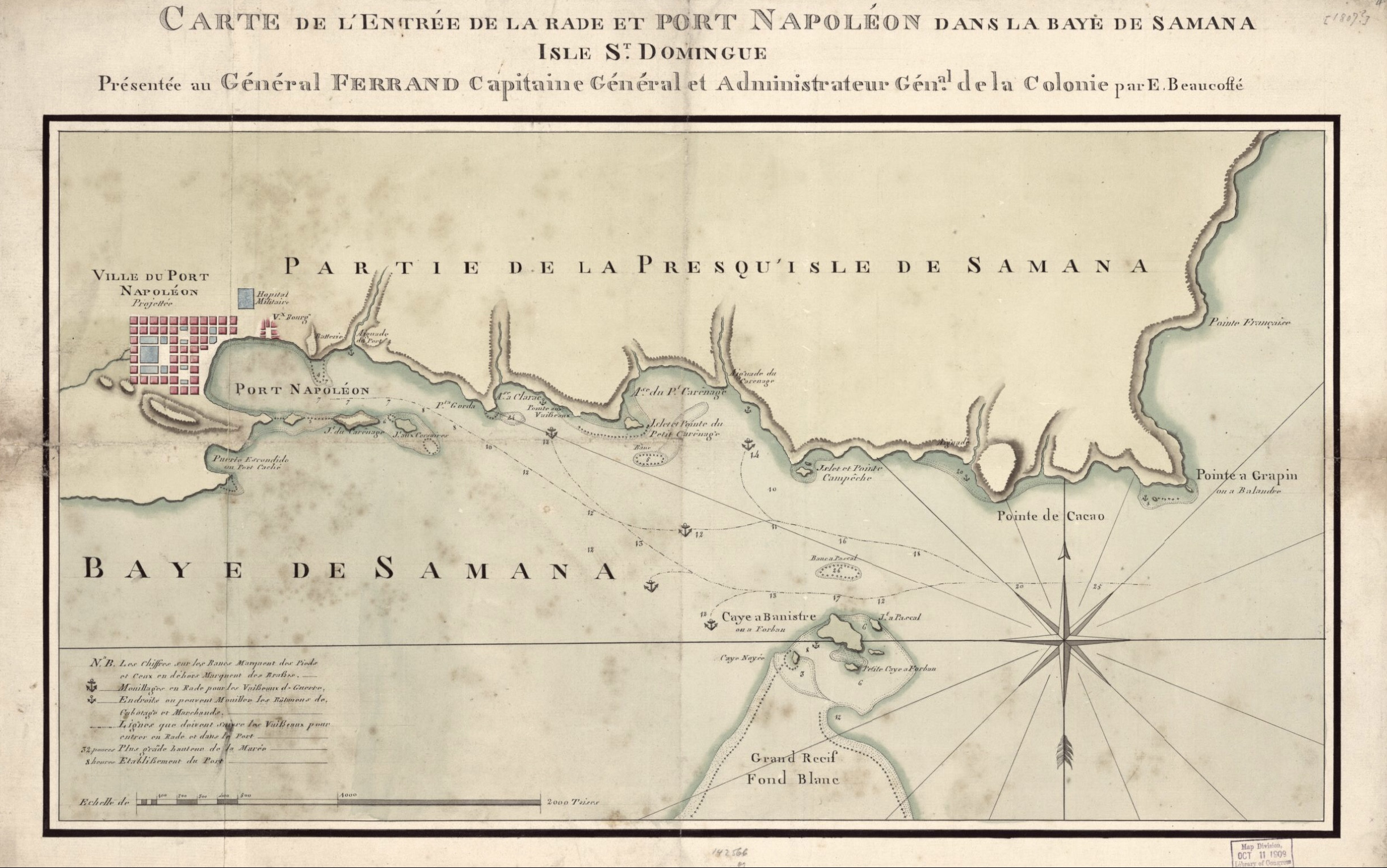

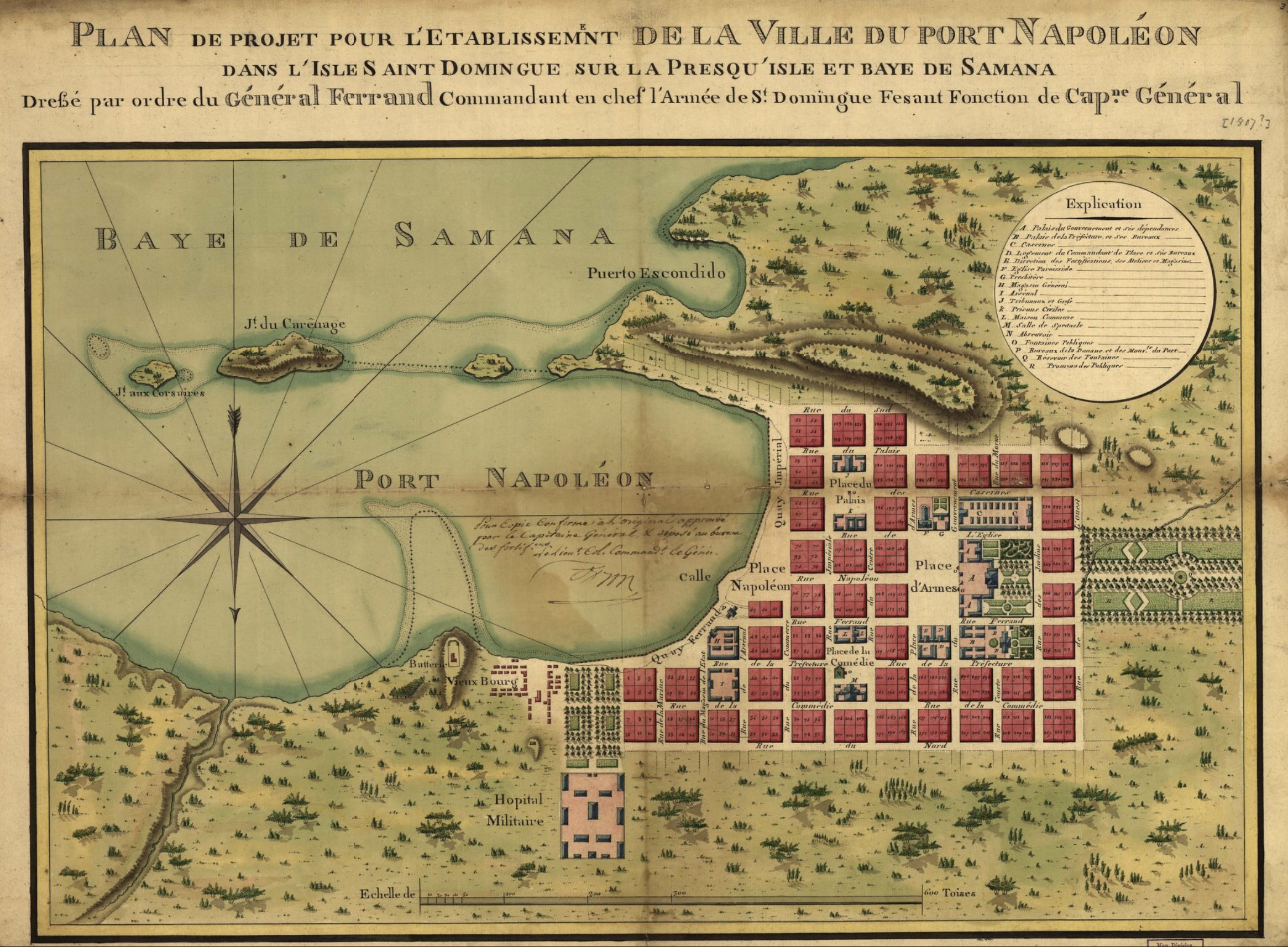

Furthermore, as a result of the war, the productive apparatus of the western part, which had been a model of sustained wealth creation, was devastated and rendered useless, with an immediate political consequence: the proclamation of independence on the 1st. January 1804 by the triumphant leaders led by Dessalines, and the designation of the latter as "Governor General for life of the island of Haiti" (10). In the eastern part, General Lois Ferrand, for his part, in command of an important stronghold of the French army that had refused to capitulate, left Montecristi for Santiago and then for Santo Domingo, relieving Governor Kerverseau from command. and designating himself "Commander in Chief of Santo Domingo" and "Interim Captain General." Its object was, of course,

Ferrand issued on January 6, 1805 a decree authorizing civilians and soldiers from "the departments of Ozama and Cibao" to pursue "and take prisoners" in "the territories occupied by the rebels" to "all those of the one or of the other sex that does not exceed the age of fourteen years ”, which from now on“ will be the property of the captors ”. For its part, the government of the nascent Haitian State postulated, like its colonial predecessor, the "indivisibility" of the island, and based on it, taking the aforementioned decree as a pretext, attacked the eastern part in March 1805 with a powerful army of 30,000 men with divisions led, separately, by President Dessalines and Generals Petion, Christophe and Geffrard, who besieged the city of Santo Domingo between the middle and the end of that same month (11). The siege lasted 22 days. It was raised on the 28th by the fears generated in Dessalines by the accidental presence in Caribbean waters of the French squadron led by Rear Admiral Missiessy, which he thought could be part of a larger force that was landing in Haiti at that time.

Thus began the Napoleonic phase of the so-called "French Period" in the history of the eastern part, while the idea was consolidated among the dominant sectors of Haiti that the ostensible weakness of Haiti as a territorial entity and national community constituted a danger to the existence of your state. Such an idea would be, from now on, the conviction axis of Haitian policy towards the eastern part. During this period, the Spanish colony on the island of Santo Domingo was governed, formally or informally, by Napoleonic rationality (through laws that had application in overseas territory), the provisions of Ferrand and, later, although for a short time, those of General Dubarquier, his replacement.

Ferrand would try to govern the colony in a paternal way, respecting Spanish customs and developing a great reconstruction work throughout the year 1805 that involved the promotion of coffee production, the revitalization of the exploitation of wood forests and the reduction of taxes, which in principle created an atmosphere of trust and tranquility and made it possible for many inhabitants to collaborate (12). However, that promising atmosphere began to be cracked, first, by Ferrand's disposition, at the end of 1807, to prohibit the trade (especially of animals) with Haiti, which provoked angry protests from the merchants of the Spanish colony; and later, by Napoleon's invasion of Spain, in January 1808, and the subsequent kidnapping of King Ferdinand VII,

The eastern part became a hotbed of conspirators against French rule, but two of them in particular would stand out: Juan Sánchez Ramírez, a wealthy landowner who had immense possessions in Cotuí and Higuey, who dedicated himself between the summer and autumn of 1808 to travel the country trying to recruit proselytes for a pronouncement; and Ciriaco Ramírez, a native of the South, who organized an uprising in October 1808 that was revealed by the occupants. Both leaders were subjected to constant surveillance and persecution by the authorities.

On the other hand, in Spain the resistance against the French occupation had quickly turned into a patriotic contest, and the Governing Board set up to conduct it had officially declared war on France, an event that became known in the colony and gave greater encouragement. to the conspirators, who, from before, in the person of Sánchez Ramírez, were encouraged by Toribio Montes, governor of Puerto Rico. His open support had been produced from August 1808, when he declared war on Ferrand.

Thus, with the support of Montes and the two leaders that Haiti had at the time (Alexander Petion and Henri Christophe), the conspiracy advanced, to the point that in the South there were serious armed confrontations between French and native Spaniards. But the decisive battle would be that of Palo Hincado, recorded on November 7 on the outskirts of El Seibo, in which a thousand combatants led by Sánchez Ramírez faced off against six hundred regulars led by Ferrand. Both the courage of the troops led by Sánchez Ramírez and the deception of Tomás Carvajal Martínez to Ferrand played a leading role in this battle (he offered the support of two hundred spear horsemen under his command who then turned their weapons against the French). This deception and the subsequent defeat would cause the suicide of Ferrand (13).

However, the Napoleonic stage of the "French Period" in the eastern part would continue, now under the rectory of General Dubarquier, until July 1809, when the French authorities, exhausted and virtually defeated by the siege in the city of Santo Domingo that Sánchez Ramírez (who now had the support not only of the Puerto Rican authorities but also of the English naval power, deployed on the island) from the final days of November 1808, capitulated before the troops led by British commander Hugh Lyle Carmichael after refusing to do so before the Creole leader.

Between July and August 1809, the eastern part was in fact placed under the authority of the representatives of the English monarchy, and after huge negotiations between them and the Creoles headed by Sánchez Ramírez, unemployment was agreed upon under the commitment that the British war expenses (supposedly amounting to the sum of 400 thousand pesos at the time) were reimbursed and they were allowed to use the island ports under the same privileges that Spanish ships had ... But this, naturally, is another chapter of our history.

- Price Mars, Jean, “The Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic”, p. 32, Dominican Society of Bibliophiles, Santo Domingo, 1995.

- Bosch, Juan, “From Christopher Columbus to Fidel Castro. The Caribbean, imperial frontier ”, p. 417, eleventh Dominican edition, Editora Corripio, Santo Domingo, 2000.

- These figures are from Price Smart. Other authors differ from them.

- Price Mars, op. cit., p. 3. 4.

- Campillo Pérez, "Dominican Electoral History (The cricket and the nightingale)", pp. 129, 130 and 131, fourth edition, JCE, Santo Domingo, 1986.

- Franco Pichardo, Franklin J, "History of the Dominican people", p. 153, second edition, Editora Taller, Santo Domingo, 1993.

- Price Mars, op. cit., pp. 35.

- Leyburn, James G, "The Haitian People," p. 43, first Spanish edition by Juan Manuel Castelao, Editora Claridad, Buenos Aires, 1946.

- Price Mars, op. cit., pp. 41 and 42.

- Price Mars, op. cit., p. 51

- Cassá, Roberto, "Social and economic history of the Dominican Republic", volume I, p. 159, Editora Alfa y Omega, Santo Domingo, 2000.

- Moya Pons, Frank, "Manual of Dominican History", pp. 203 and 204, 12th edition, Editora Corripio, Santo Domingo, 2000.

- Bosch, Juan, "Palo Hincado: a decisive battle", contained in "Historical Topics", volume I, pp. 19-26, Editora Alfa y Omega, Santo Domingo, 1991.

computer translated from:

Napoleón Bonaparte en nuestra historia

Aunque entre la isla de Santo Domingo y Francia hay una distancia de aproximadamente 7 mil doscientos kilómetros y Napoleón Bonaparte siempre tuvo a Europa como interés fundamental en sus correrías de